Ecce Homo. Adam Chmielowski’s Journey through Positive Disintegration

Author: Elizabeth Mika

I would like to thank Sister Krzysztofa Maria Babraj from the Order of Sisters Albertines in Krakow for providing me with materials about Brother Albert’s life.

Theoretical Considerations

Studying biographies of eminent individuals and personality exemplars using the TPD-based conceptual framework allows us to describe developmental forces shaping their lives and map out certain developmental trends that may deepen our understanding of human psychological growth in its multilevel and multidimensional richness and variety.

The life of Adam Chmielowski, a.k.a Brother Albert, an artist-turned-monk-turned-humanitarian, exemplifies a case of global and accelerated personality development through positive disintegration. As such, Chmielowski’s case is invaluable for students and researchers of TPD as it provides an empirical validation of the theory’s basic tenets. Apart from its scientific value, however, Chmielowski’s life is even more an inspiring example of things developmentally possible for those of us engaged in a search for authentic existence.

According to the Theory of Positive Disintegration, personality growth through positive disintegration is guided by the developmental instinct. As Dabrowski says, “The whole process of transformation of primitive drives and impulsive functions into more reflective and refined functions occurs under the influence of evolutionary dynamisms which we call the developmental instinct.” (Dabrowski et al., 1973, p.22). The instinct of development arises from and eventually transcends the instinct of self-preservation in individuals endowed with high developmental potential. It contains “separate nuclei of transformation; of possible disintegrative processes; of the inner psychic milieu, special interests and talents; and the nuclei of the fundamental essence of human existence – i.e. the most substantial individual human properties.” (ibid., p.23). The multilevel approach of TPD differentiates two distinct multilevel parts within the instinct of development: a lower creative instinct and a higher instinct of self-perfection.

The creative instinct encompasses and expresses various dynamisms characteristic of both UL and ML disintegration, while the instinct of self-perfection is associated with higher dynamisms expressive of organized multilevel disintegration, and is the dominant force in the later stage of development, the borderline between levels IV and V. Dabrowski considered the instinct of self-perfection “the highest instinct of a human being” (ibid., p. 32).

As Dabrowski says, “The creative instinct can operate at the stage of unilevel disintegration. The multilevel dynamisms and hierarchies are not as indispensable in its development as in the instinct of self-perfection. The creative instinct does not necessarily express universal, fully rounded development. Very often it is based on partial disintegration. In this instinct sensual and imaginational hyperexcitabilities play the greatest role. Inner psychic transformation, and especially the transgression of the psychological type and the biological life cycle do not show the necessary globality; they are partial only. The instinct of self-perfection does not usually embrace a narrow area, but the whole or at least the greater part of the personality of the individual. All its functions are shaped so as to “uplift” man. It is the expression of the necessary, self-determined “raising up” in a hierarchy of values toward the ideal of personality.” (ibid., p.30)

The interplay of these two developmental forces, which can act in concert and in opposition, is responsible for creating a rich inner milieu, full of contradicting desires and ripe for inner conflicts, which, in turn, lead to and guide disintegrative processes of both unilevel and multilevel kind. It can be argued that an assessment of the strength of both instincts (creative and self-perfection) would allow us to make predictions about the shape and direction of an individual’s development. Such predictions, however, by necessity would be crippled by uncertainty inherent in our judgment of the causes and results of complex human behavior.

In Adam Chmielowski’s case, we can follow the evolution of his developmental instinct throughout his life and observe the shaping of his personality through both the instinct of creativity, dominating the first part of his life; and the instinct of self-perfection, which although present almost from the beginning of his life, gradually gained strength and became the primary developmental force in its later part, after a dramatic period of global positive disintegration. As his first biographer wrote, “His life was full of contradictions and surprises.” (Kaczmarzyk, 1990, p.7) Very early on, we can observe in Adam manifestations of a high developmental potential: high intelligence, abundant forms of all five types of overexcitabilities, artistic and humanistic interests, and, already in childhood, precursors of multilevel dynamisms seen in his attitudes of responsibility, honesty, and a desire for authenticity and self-improvement. At the same time, the richness of his developmental potential set the conditions for inner conflicts and contradictions, among which the conflict between his creative instinct and emerging instinct of self-perfection took the center stage for many years of his life.

Adam’s Childhood and Youth

Adam Chmielowski was born on August 26, 1845 in a small Polish town of Igolomia.

His parents belonged to impoverished Polish nobility. His father, Wojciech, was a customs administrator in Igolomia; his mother, Jozefa, a delicate and religious woman, ran their household with tact and a sense of humor. Adam was a beautiful child, whose intelligence, mature sensibility and physical beauty never failed to impress others. His own father wrote this about his 1-year-old son in a letter to his relatives:

“My son is a big man and I can count on him completely in so many respects; he is very sensible, understands everything, walks by himself, even though they try to hold his hand. A beautiful child; I’m looking at him not through the father’s eyes, but (…) he is so lovely and admirable that all who see him always say they have never seen such a beautiful child.” (Kluz, 1981, p.14)

Little Adam was christened at 2, and as one story goes, his parents invited beggars congregating around the church to be his godparents and secure the blessing of the poor for their son.

When Adam was 8, his father died of tuberculosis, leaving his widow with four young children and little money, since most of their finances were spent on Wojciech’s doctors and medications. Adam was sent to Petersburg where he could get free education as a child of a government employee. At 11, he was enrolled in a military school, where he excelled in studies and self-discipline. In spite of his admirable attitude toward his studies, he greatly missed his family and often cried at night. When he came home on vacation, his mother was terrified to find out that his already excellent – and growing — mastery of the Russian language was threatening his ability to use Polish. She decided not to send him back to Petersburg, but enrolled him instead in a Polish gymnasium in Warsaw.

Mrs. Chmielowska, not even 40 yet, died in August 1858. The fate of the four Chmielowski children from now on would be decided by a family council consisting of relatives and friends of the family.

The Soldier

Adam’s next educational step was the Institute of Agriculture and Forestry in Pulawy, the only academic center open to Polish youth in the region.

In 1862, when Chmielowski began his studies there, the conflicts between Poles and occupying Russians grew to dangerous levels. On January 23, 1863, the tensions culminated in the January Uprising, one of the most heroic events in the history of the Polish fight for freedom. Chmielowski, along with almost all the students of the Institute, joined the uprising. He was 17 and ½. Adam’s participation in the Uprising was characterized as much by his personal courage, witnessed and reported by his comrades in arms, as by several unusual strokes of luck that helped him stay alive in very dire circumstances. He fought, he was arrested, escaped from prison, joined the resistance again, fought again, was seriously wounded in a battle of Melchow, and was captured by Russians, who, instead of killing him, as it was to be expected, treated his wounds. Unfortunately, part of this treatment involved amputating his left leg – without painkillers. The only means of easing the pain was a cigar, which Adam swallowed whole, still burning, in the agony of the amputation.

His friends from this period remembered him as a courageous and honest young man, liked by everyone, who “with his joyfulness and enthusiasm energized in the saddest moments the whole camp.” (Kluz, 1981, p.33)

Adam’s family was able to negotiate his release from the Russians, and, in order to protect him from possible reprisals for his involvement in the failed uprising, sent him to Paris in 1864, with very meager financial means, which were used partially to purchase an artificial leg for him.

From Paris, young Adam returned to Warsaw, where he wanted to enroll in an art school. His family council, however, did not approve of this choice, believing that art was not a suitable occupation choice for a young man. They sent him to Belgium to study engineering, borrowing money for his education. Adam did not like science and engineering did not interest him at all. He returned to Warsaw, and from there, after obtaining, seemingly in another stroke of luck, a generous stipend to study abroad, he set out to Munich to study art.

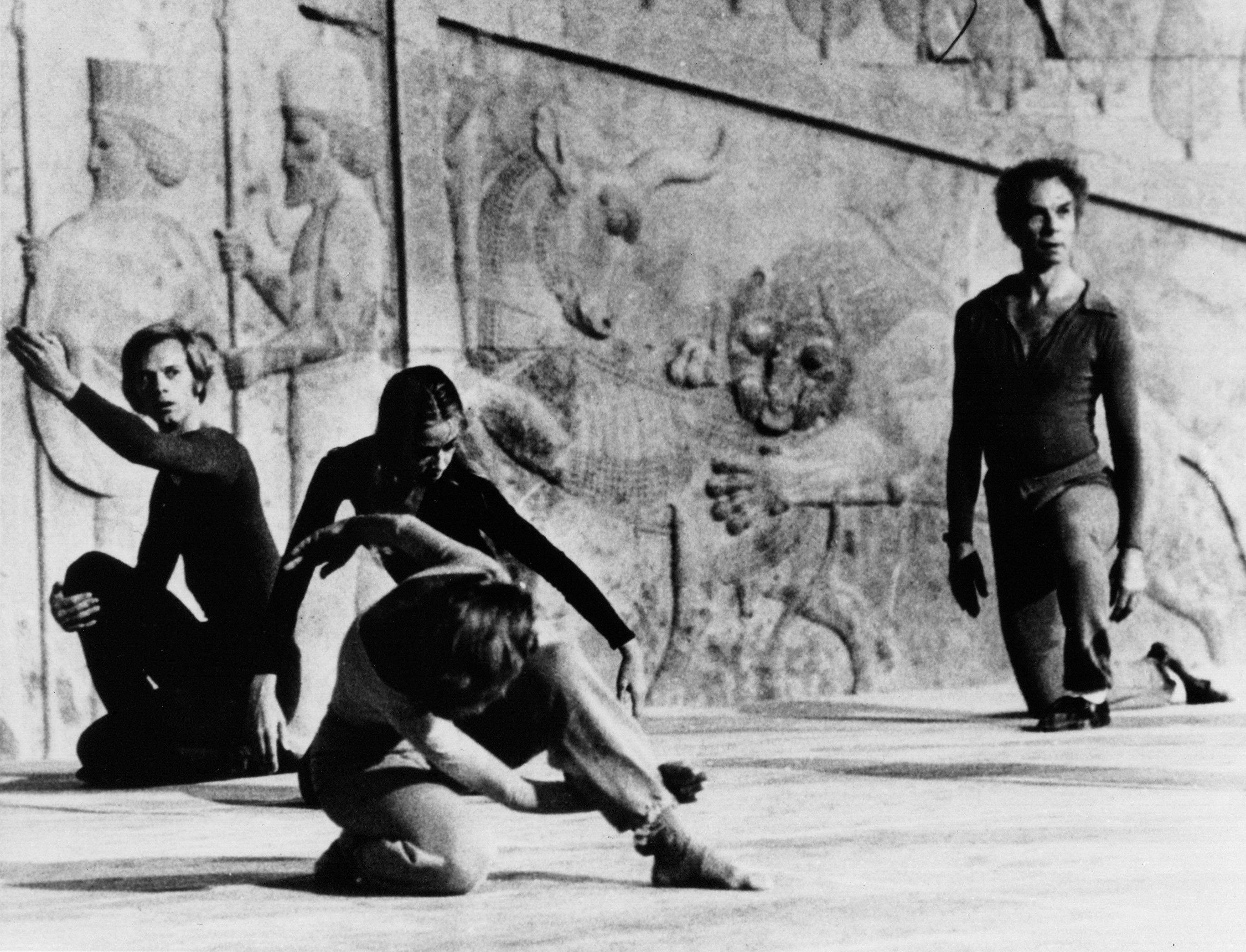

The Artist

In Munich, which at that time was home to the most prestigious Academy of Art in Europe, Adam, who was 25 then (1869), joined a group of Polish artists, who were among the Polish artistic elite – or on their way there. Jozef Brandt and Maksymilian Gierymski, two eminent Polish painters, became Chmielowski’s best friends. Adam studied hard, despite his very precarious financial standing with the academy. He worked with particular efforts on his drawing skills, which were his weakness. At that time his development intensified. His friends and acquaintances remarked on his severe self-criticism and demands from himself, and constant self-doubts, combined with a critical approach not only to his own creations, but also to art in general. He was particularly dismayed with what he saw as commercialization of art and its artifice that rendered it dishonest and superficial. To him, art was the means of expressing one’s soul. His goal as an artist was to “minimize the gap between thought and its expression in a painting” (Kluz, 1981, p.45) With the goal in mind, he put particular efforts into perfecting his skills. He approached his work with the characteristic honesty and obsessive devotion. Many of his letters that survived from this period portray Chmielowski as much devoted to art as lamenting, often with a mocked desperation, over its demands on one’s life.

His first exhibited work, “An Italian Siesta,” was received with mixed reviews: Some appreciated its subtle and poetic harmony, the original use of color, and a mysterious subject that stimulated imagination; while others criticized it as unfinished and amateurish. Chmielowski was undaunted by the criticisms. He continued working and learning, searching, critically, for his unique style:

“They say that style and the man are one and the same; I don’t know how true this is, but that a painting and the one who paints it are the same, of that I’m completely convinced. (…) However God made one, that’s how one will paint.” (Kluz, 1981, p.65)

His own style evolved through mythological inspirations, fairy tales, and influences of Greek and Italian cultures toward sad, mystical landscapes and religious scenes. He saw the essence of art to be an expression of the human soul. In his 1879 essay, “On the Essence of Art,” Chmielowski defined a work of art as “any honest and direct expression of human soul” in an artist’s works. Authenticity mattered more than acquired skills, according to Chmielowski. As his artistic work progressed, it became increasingly more connected to the contents of his inner milieu; it not only illustrated his current state of mind, but also heralded changes to come.

During his stay in Munich, Adam’s social contacts strengthened. He formed exclusive and enduring friendships with his Polish fellow artists, especially with Maks Gierymski, whose diaries preserved recollections of a very close, though at times conflictual relationship between the two men. The conflicts had largely to do, it seemed, with Adam’s growing religious fervor and seriousness toward life and their work. At that time, he became a sought out authority among his friends not only as an objective and wise critic of their work, but also as a great companion appreciated for his personal charm, kindness, loyalty and a great sense of humor, especially for his penchant for practical jokes (one of them involved putting his artificial leg under the wheels of an oncoming carriage).

At the same time, along with continuing self-doubts, other desires began to take shape in his feelings and thoughts. “Can one also serve God while serving art? Christ says that one cannot serve two masters. Though art is not money, it is not god either – rather an idol. I think that serving art always amounts to idolatry, unless one can, like Fra Angelico, use his art and talent and thoughts to devote to God’s glory and paint holy images; but one should, like him, purify oneself and sanctify and enter a monastery, because it is difficult to find such holy inspiration in the world-at-large. These questions are old things, no doubt; but when one grows older and starts gaining some wisdom, one would gladly learn which one is his path and what will matter in his life. It’s a very beautiful thing – the holy pictures; I would very much like to ask God to let me make them, but only from true inspiration and this is not given to just anyone. So much suffering and best blood goes into painting. If only there was some good use for it.” (Kluz, 1981, p.71).

Descriptions of Adam as a young man portray him as tall, well built, handsome (beautiful), with regular facial features, large expressive eyes, and a long beard. Helena Modrzejewska, a famous Polish actress and a very close friend and promoter of Chmielowski and other Polish artists of his generation, described Adam this way:

“Chmielowski has been a walking example of all Christian virtues and deep patriotism – almost without a physical body, breathing poetry, art and love of one’s neighbor, a nature so pure and free of egoism, whose motto should be: happiness for all, and glory to art and God!” (Kluz, 1981, p.89)

Here is another characterization, by a friend artist:

“Adam was a strong well built man, dark haired, with a straight nose and gentle blue eyes. His beard and mustache dark, closely cropped. His behavior was aristocratic. Sometimes a grimace showed on his lips. He was about thirty years old. (…) His stomach problems grew stronger due to his lack of physical activity and Adam was frequently upset. He was irritated by everything and displeased at those times. He only grew livelier in good company, because he was such a refined conversationalist. He spoke fluent German and French. In his good moments, he painted such impressions that they simply blew us away. Unfortunately, he destroyed almost all of them in his moments of depression. Of course, he never made any money and he did not care about it.(…) He was the smartest among us painters. Even though he could never finish anything and destroyed magnificent works. (…) His color sensitivity was so great (…) nothing made him more upset than disharmony of colors. (…) When he noticed a false tone, he had a wry face, as if he bit a pepper seed, and his mood was spoiled for some time.” (Kluz, 1981, p. 85 and 86)

The Munich period ended for Chmielowski sadly with the death of his beloved friend, Maks Gierymski, in September 1874. Gierymski died in Chmielowski’s arms, and Adam was one of only two people present at his funeral.

After Munich, Chmielowski traveled to Krakow and Warsaw, and spent time with friends, continuing his artistic work. Leon Wyczolkowski, a painter and Chmielowski’s friend and roommate in 1879 in Lwow, had this to say:

“Chmielowski was our teacher; a refined man, a deep mind (…) A sophisticated person, a passionate artist with lots of verve. He did a salto mortale in his life – not everyone can do it. (…) An interesting life. Never discussed his love life with me. Funny, humorous, an extraordinary story-teller.” (Kluz, 1981, p. 100)

Chmielowski’s love life is a mystery, but some accounts link him romantically to Lucyna Siemienska, daughter of his benefactor, Lucjan Siemienski. There are numerous letters and notes from Chmielowski to Lucyna, who looked favorably upon Adam’s interest, as her sister reported in her recollections of Chmielowski. Her father, however, unhappy with the idea of a struggling painter as a candidate for his son-in-law, married Lucyna off to a rich landowner. After that, Chmielowski never mentioned Lucyna’s name.

As Chmielowski continued his artistic career, he grew more dissatisfied with both his artistic endeavors and his life in general. “What can I write you about myself,” he said in a letter to Lucjan Siemienski, “only that I keep painting with passion. I am a rather crazy individual, it seems, because I do not feel too good in the real world, so I run away into trifles that I create in my imagination and I live there among them; it is a rather funny way to chase away worries, and given my inherent slackness, a practical one. But for how long?” (Nowaczynski, 1939, in Ryn, 1986, p.546). This self-assessment shows Chmielowski’s maladjustment to everyday reality, with the concurrent positive adjustment to higher level world of his ideals. The growing gap between the two, however, was taking an increasing toll on his physical and mental well being:

“I’ve lost my joy and my carefree attitude, and I’m afraid for myself because of my fancy tastes;” “I’m very nervous and somewhat unwell…, my mind gets sick sometimes; it’s a common malady among people, even though they do not admit it, and they only notice it when a patient has to be put away in a crazy house.” (Ryn, 1986, p.546)

The processes of disintegration, intensifying in his inner milieu, were noted by others who reported changes in his demeanor; they were also illustrated in his art, which began to grow darker in tone. Paintings such as “An Abandoned Church,” “A Grave of a Suicide Victim,” “A Funeral of a Suicide Victim,” (he destroyed the latter two), and “An Abandoned Horse” expressed his growing sadness, inner loneliness and awareness of his distance from his true self and from God. It is characteristic that his landscapes painted during this period are suffused with the same mood of loneliness and desolation.

His treatment of human subjects is also interesting. When we look at Chmielowski’s portraits, we notice immediately that many of their subjects do not look directly at the viewer – they are either turned away or aside, or gaze longingly in the distance – too remote and withdrawn, too absorbed in their own inner lives to pay much attention to the outside world. Those faces that are in full view strike us with their overwhelming sadness that has almost a pleading quality to it. No matter what the theme of his painting, people he painted, almost all of them, look like lost or abandoned children, isolated in their sadness from themselves and from the world.

Perhaps not surprisingly, portraits and photographs of Chmielowski, himself an orphan, express a similar emotional tone. They show an emotional and spiritual evolution of the man in a strikingly clear manner. We see him early on as a thoughtful, searching yet hopeful young man, whose life appears to him full of possibilities. As he grows older, sadness hinted in his eyes grows, erasing the subtle signs of optimism and hope visible in his youthful portraits. The sadness takes on the tone of despair and turns into unbearable suffering, culminating in the period of Chmielowski’s mental crisis and expressed, in his art, by the hauntingly beautiful painting, “Ecce Homo.” Chmielowski’s picture taken right after his release from the mental hospital shows a man who appears lost to himself and the world, transformed – and emptied, but not broken — by the agony of prolonged mental suffering. The picture, it is important to note, appears to be taken when Chmielowski was still in the throes of depression which was to lift several months later. Sunken cheeks in a sickly, thin face; the same sad, deep eyes, which, although no longer hopeful, still contained glimmers of resolve — the severity of his suffering was palpable.

Throughout his whole life Chmielowski created over 60 oil paintings, numerous watercolors, drawings and sketches. There is no reliable record of how many of his works he destroyed. This tendency to destroy one’s art is an expression of the partial death instinct and the intensifying instinct of self-perfection, frequently observed in lives of individuals with high developmental potential in the periods of accelerated development. On the symbolic level, it can be interpreted as a need to destroy one’s old values and ways of thinking, even though the new ones are not yet formed, but barely intuited.

Chmielowski’s work in general received mixed critical reviews. He was universally praised for his innovative use of color and light, but some held against him his lack of strong drawing abilities and what they perceived to be a lack of substance and moodiness of his artwork. Ironically then, his one painting that received excellent reviews was one of two of early religious paintings, “A Vision of St. Margaret.” This particular painting, though critically acclaimed, appears to be imitative in nature and lacks the authenticity that Chmielowski considered to be the essence of art.

About the same time when Chmielowski made “A Vision of St. Margaret,” in 1879, he began painting “Ecce Homo,” his favorite painting, one on which he worked for several years, took with him everywhere and never really finished.

“Ecce Homo” is a painting is like no other. It mesmerizes with the depth of feeling expressed in Jesus’ face and makes even a reluctant observer stop and ponder both the mystery of Christ’s life and suffering, and the artist’s skill in depicting it. It also makes one wonder what kind of emotional work went into creating this painting, which is described as follows by Leon Wyczolkowski:

“The deepest expression of Christ Chmielowski showed in Ecce Homo. It’s a gray day, it’s raining. Christ tortured, his eyes sunk deeply inside. That’s what happened and what had to happen. Christ exhausted, mistreated, spat on, wrapped in a purple cloth, but his eyes are looking inward.” (Kluz, 1981, p.106)

Ecce Homo – Behold the man — are words of Pontius Pilate presenting the tortured Christ to the public, demanding his execution. These words have a deeply symbolic meaning and it is no mistake that Chmielowski chose them as the title of his most important and most moving painting, the one which ushered a new, and very dramatic, period of his life.

In September 1880, Chmielowski entered a Jesuit convent, to a great surprise of his relatives and friends. He did not confide his plans to anyone, but just before taking this step, he sent letters to his closest friends, in which he explained his decision as dictated by his serious concern over the state of his soul and his future, eternal life. In those letters, he exhorted his friends to abandon the “aesthetic silliness” of art for art’s sake, and devote their lives to God. He also expressed hope that his artwork from now on would be better and more prolific.

This is what he wrote to Helena Modrzejewska:

“I could no longer stand this bad life, with which the world is feeding us, I couldn’t bear the heavy chains any longer. The world like a thief steals every day and every hour all that is good in our hearts, steals our peace and happiness, steals God and heaven. For all this I’m entering the convent: if I lost my soul, what else would I have had left?”

(…) Even though I don’t know whether I have a talent or just a tiny gift, I know for certain that I’m on my way back from the banks of this sad river that has swallowed so many victims, and still keeps swallowing more! Art and only art, anything for her smile, or a shadow of her smile, for only one rose from the wreath of this goddess, because it brings fame and wealth and personal satisfaction – no matter the rest; one loses family, morality, one’s country, one’s relationship with God in this crazy race; one loses everything that’s good and holy, years are passing, physical body deteriorates, and with it the so-called talent – what remains is only despair or idiocy on the bottom of one’s skull; and beyond that – death; but even if only death and nothingness, but not even that, because the soul never dies.

(…) I’ve thought for a long time in my life about who is this queen art, and I’ve understood that it is only a figment of our imagination, or rather a horrific nightmare which prevents us from seeing the real God. Art is only an expression and nothing else, works of the so-called art are only physical manifestations of our soul, they are only our works – and it’s a good thing we make them, quite simply, for this is a natural way to communicate and understand each other. But if in those works we pay honors to ourselves and give everything away, then, even though it is called the cult of art, in reality it is only masked egoism; and to worship oneself is the stupidest and most abominable kind of idolatry.” (Kluz, 1981, p.112).

Though the letters offer a clear indictment of his previous lifestyle and his pursuit of artistic career, they are also very optimistic and express his joy of finding the right path for his life. (“In thoughts of God and future things I’ve finally found happiness and peace, which I sought in my life without success.” (…) “I’ve started a novitiate, I feel very happy.” (…) “I’m sending you good and joyful news, joyful for me beyond all words, I’ve entered a convent.” Kluz, 1981, p. 113)

The Crisis

A truly authentic attitude has three methods of resolving intellectual and emotional tensions: mental illness, suicide, or struggling toward the absolute despite great difficulties and few results. (Dabrowski 1972, p.18)

Chmielowski took the habit on October 10, 1880. In April 1881, he was asked to leave the convent. The reason: mental illness. Doctors treating Chmielowski quoted the Jesuits’ opinion about him:

“They noted a gentle and well educated character, in general well developed and rich, with certain eccentricity of affects and imagination both in his ideas and religious asceticism. The illness occurred together with strong pangs of conscience, self-condemnation, terror of his own death and eternal damnation, and thoughts about his unworthiness of being a Jesuit.” (Kaczmarzyk, 1990, p.41)

On April 17, 1881, Chmielowski was placed in a mental hospital in Kulparkowo, near Lwow, where he stayed till January 22, 1882. He was diagnosed with “hypochondria, melancholy, religious insanity, anxiety, psychic oversensitivity” (Kluz, 1981, p.113) As reported by his doctors, he was able to logically present his symptoms of depression and anxiety, did not eat and had to be fed by force, did not sleep well or at all, and complained of stomach problems. He also stopped smoking at that time, and some speculated that this brought on the nervous attack.

When the hospital stay failed to improve his condition, Adam was released to his brother, Stanislaw, and stayed with his family in Kudrynce throughout the summer of 1882, still ill, silent, completely withdrawn, barely existing. His doctors as well as his friends considered his state hopeless. Jozef Chelmonski, a fellow artist, visited Adam in the hospital and wrote this to his wife:

“Adam Chmielowski went crazy in the Jesuit convent and now is in a mental hospital. I was upset by this, but now I will talk to him, he is like a dead man.” And, in a later letter:

“In Lwow, I saw Adam Chmielowski, who is with the crazies. He has awfully deteriorated, probably won’t survive.”(Kaczmarzyk, 1990, p.43)

Those who saw him during that time recalled a man “deeply buried in sadness, who spent all his days in his room, silent, despondent, refusing food or drink, immersed in horrible inner suffering. How long it lasted, I don’t know, but any attempts to take him out of his apathy were futile; he did not dare to take holy sacraments, did not leave the house, nor dared to step over the threshold of a nearby church.” (Kluz, 1981, p.114)

A friend, quoted in Ryn, said:

“Adam withdrew completely from other people, even from contacts with the closest family; not only did not spend time with anyone, but fell silent, mute, as if he completely lost his hearing and ability to talk. Usually he sat in his room, where his food was brought, sometimes he walked like a shadow in the garden and then came back to his room, deep in his sadness, bitterness and utter abandonment, as if in the agony of soul. This state lasted weeks and months, maybe over half a year. Others around him in Kudrynce got used to it and left him alone, and practically stopped caring for him.” (Ryn, 1986, p.552)

Chmielowski himself, later in life, when asked about those experiences, stated: “I was conscious, did not lose my senses, but was undergoing horrible pain and suffering and the most awful scruples. I entered the Jesuit convent, but God wanted something different for me.” (Kaczmarzyk, 1990, p.44)

There are several theories on the origins and meaning of Chmielowki’s psychological crisis. Kaczmarzyk, for example, attributes it to a drastic lifestyle change required by the Jesuits: quitting smoking, limited physical activity, requirements of the severe ascetic life were too much to bear for a sensitive nature like Chmielowski. His doctors considered a possibility of the trauma of war and his handicap as conditions contributing to his breakdown. One cannot completely discount the role of his early traumas – deaths of his parents, his participation in the bloody uprising and the loss of a limb, as well as the recent death of his closest friend, Maks Gierymski. While any and all of these factors may have, and most likely did play a role in bringing Chmielowski to the point of such a deep crisis, they certainly do not explain either the crisis itself nor its subsequent resolution.

This period of Chmielowski’s life is treated variously in materials available about his life. Some authors do not mention it at all, others talk about it very briefly, struggling with ways to understand and explain it. Some use the term “God’s trials,” others borrow St. John of the Cross’ phrase “the dark night of the soul.” There is an aura of mystery and at times slight embarrassment surrounding the mentions of Chmielowski’s illness in his biographies. One notable exception is Z. Ryn’s article devoted specifically to Chmielowski’s psychological make-up and psychiatric problems. But even Ryn makes a puzzling remark that Chmielowski’s diagnosis was ‘thankfully’ changed in years after his death – from schizophrenia to depression. “Thankfully,” because this change made possible the subsequent process of his posthumous beatification.

For those familiar with the Theory of Positive Disintegration, Chmielowski’s crisis appears to be a period of global and accelerated growth through positive disintegration – so dramatic that it took shape of a “psychic catastrophe.” It was a painful and often frightening process, but one that was developmentally necessary for Adam as it set the stage for his work at the next developmental level – of organized multilevel disintegration. It is not difficult to see in Chmielowski’s symptoms acute intensification of dynamisms of spontaneous ML disintegration: feelings of guilt; dissatisfaction with himself, augmented by a desire for self-mortification through his refusal of food; intense inner conflict; and moral scruples signaling work of the “active conscience,” which is what Dabrowski called the dynamism of third factor.

The end of Chmielowski’s illness, or the period of accelerated spontaneous disintegration, was as mysterious and sudden as was its beginning. Dabrowski calls such a dramatic realization that affects permanent developmental changes in behavior a “sudden dynamic insight.” (Dabrowski, 1998, p.69).

In August 1882, almost a year and a half after the onset of his illness, Adam underwent a striking and unexpected transformation in his behavior. As the biographical story goes, he overheard a conversation that his brother had with a local priest who came to visit their house. Afterwards, as a family friend recalled, “When a servant entered his room with food, Adam unexpectedly spoke to him, asked him to prepare a horse-driven cart, because he had to leave. The stunned boy could not believe his ears hearing Adam speak. In the meantime, Adam got into the cart and galloped beyond the Russian border toward Kamieniec Podolski, to a very decent priest, with whom he confessed his sins and took Holy Communion. And he returned to Kudrynce changed beyond recognition. Happiness and joy and deep peace emanated from his face, love and affectation of gratitude, goodness and strange compassion toward people.” (Lewandowski, in Ryn, 1986, p.554)

His family was amazed by his transformation, “seeing him constantly happy, sharing, simple, beaming with joy, though still needing solitude.” (Ryn, p.554)

A priest who met Chmielowski after the crisis, had this to say about him:

“A tall well built man, his facial features appeared taken from some ancient painting. Closely cropped beard and mustache seemed to add severity to him, but this impression immediately disappeared when you looked into his peaceful eyes, gentle and blue like the sky. His behavior was simply captivating, full of unusual sweetness and charming simplicity. (…) He had a heart of gold and because of that was able to feel all human misery with astounding subtlety.” (Kaczmarzyk, 1990, p.47)

The transformation was permanent. From now on, Adam would never again experience depressions or inner doubts. As Ryn stresses, the inner transformation took place through his illness, “but in full consciousness and in accordance with his natural character disposition.” (Ryn, p.554) His behavior was full of simplicity and free of any unusual traits or strange tendencies. The nature of this transformation, according to Ryn, was not accidental, but was prepared by long years of studying and searching, and inspired by works of St. Francis and St. John of the Cross, whose temperaments and ideas were close to his own spiritual make-up.

Brother Albert – The Atrophy of Egoism

Only after the majority of our aims and goals are reduced to ashes, do some remain to light the way toward love without self-satisfaction. (Dabrowski, 1972, p. 19)

Adam felt a renewed enthusiasm for painting, but also for social action and deepening religious devotion. He joined a Franciscan order and traveled spreading the teachings of St. Francis among the people of Podole. He painted a lot – created about 10 oil paintings and 13 watercolors at that time. But his missionary activity raised suspicions among the Russian government officials, and in order to avoid an arrest, Chmielowski had to flee to Krakow.

Chmielowski arrived in Krakow in the fall of 1884. He rented an apartment on Basztowa Street where he had an art studio, which he transformed for some time into a small convent. He continued painting, but now mainly to earn money, which he could later share with the poor and homeless. It is worth noting that his art at that time focused mainly on landscapes and portraits of family members. It had no traces of the previous sadness and moodiness, and lost the intensity of expression characteristic of his pre-crisis work.

Quite by accident, Adam stumbled upon a place that was to change his life forever. After a ball one night, in a company of two aristocratic friends, Chmielowski went to visit a shelter for the homeless in Kazimierz. The shelter was in a post-military hut run by the city of Krakow, where the homeless and poor could find a place to sleep during winter months.

What Chmielowski saw there shook his conscience. The scenes in the shelter reminded him of the Dante’s hell, according to one of his friends who recalled Adam’s impressions. Witnessing drunken orgies, violence – physical and sexual, dirt and mind-boggling poverty of the place made Chmielowski leave with a strong desire to help the shelter’s inhabitants. He made a heroic decision – took on a Franciscan habit and a new name – Brother Albert – and eventually moved into the shelter with the homeless. He did not yet abandon art, but as his work on behalf of the homeless intensified, he had less and less time to devote to it.

The city of Krakow, or rather the city council, was quite pleased with Brother Albert’s decision to take care of its homeless and poor. The council members even prepared a contract for him, in which they gladly gave him the whole responsibility for running the shelters while retaining full control over his actions. They also gave him a little money, asking that he gave back anything leftover (!). Brother Albert was not paid for any of his work. His decision inspired others who wanted to help. And so he started gathering friendly souls around him, willing to share his duties. This was the very beginning of the Brothers of the Third Order of Saint Francis, Servants to the Poor, later called the Albertines, or the Gray Brothers. Under Brother Albert’s guidance, they organized shelters, soup kitchens, workshops where they could learn job skills, and other institutions for the poor and needy. They depended completely on charity. A community of Albertine sisters was established some time later.

The work of mercy started by Brother Albert spread thanks to his tireless efforts and undying faith in their necessity. He oversaw each new endeavor, provided moral and spiritual guidance to brothers and sisters Albertines, and continued endless actions directed toward bettering the fate of the poor. Those included writing letters to city officials, writing press articles describing the dire situation of the poorest members of the society, occasionally participating in charity balls and art auctions, and as always, asking and if necessary, begging for money. The Albertines took vows of poverty and literally possessed nothing. Brother Albert was very adamant about this particular vow and reacted strongly whenever he felt that a brother or sister violated it. His love of poverty was radical indeed, as was his total devotion to the poorest, wretched and humiliated. He wrote much on the subject:

“Even if I discovered mountains of gold and silver, I would not be as happy as I am with this priceless treasure of total poverty.” (Kaczmarzyk, 1990, p.85) When offered a piece of land for either a convent or a shelter, he refused, saying, “We will not accept as a possession any building or place, or any other thing.” “It is better if the buildings burned down at once rather than the brothers would possess them.” (ibid.) Among his last dying words was the brief admonition: “Above all remain poor.” When seeing unnecessary luxuries, Brother Albert would become angry. He himself had practically nothing and never asked for anything for himself, nor accepted any preferential treatment for himself, even when he was sick and infirm. His love and devotion is expressed in those now famous words:

“One should be as good as bread. One should be like bread, which is laid for all on the table, from which anyone can cut a piece for himself and eat, whenever he is hungry.””(ibid. p.87)

Brother Albert never refused help to anyone, no matter the circumstances, and instructed his brothers and sisters to do the same. He trusted completely in God’s mercy and indeed there were numerous instances when help materialized seemingly from nowhere at times of hopelessness and despair.

As word of his work spread, he became a popular figure, respected and loved by all. He did have occasional detractors and armchair critics, who were eager to find fault in his work, but he dealt with criticisms with kind patience on one hand, and a strong belief in the primacy of God’s will on the other. When dealing with one aggressive campaign of lies about one of his shelters, he wrote a calming letter to Sister Bernardyna: “I have thought all this through, there is nothing to worry about, only surrender everything to God. These or similar things are everyday matters in the shelters.” (Kaczmarzyk, 1990, p.74)

This period of Brother Albert’s life is well known and described in numerous books devoted to him and his work. The limited scope of this presentation will not allow us to spend as much time on discussing Brother Albert’s accomplishments as they deserve. Kaczmarzyk’s biography, “Trudna Milosc,” (1990), is a compelling recollection of this time in his life. I would like to focus on his emotional development, which we can glimpse from his notebooks, letters and observations of others.

All who came in contact with Brother Albert during the last period of his life remarked on his warmth, his genuine interest in the welfare of others, and on his religious devotion. His own letters show a man who is unquestioningly devoted to his search for God and servitude to the poor. His loving, and also lovingly demanding, attitude toward his brothers and sisters was demonstrated in his teachings, advice and admonitions. He was authentic and direct, did not mince words when necessary to convey his message; and was uncompromising in his insistence that his brothers and sisters strictly observed the Albertines’ rules. But his admonitions, even though seemingly harsh at times, were always balanced by love and genuine concern for those toward whom they were directed.

Brother Albert developed a particularly close relationship with Sister Bernardyna, who joined the convent at 16, and later became the Mother Superior of the Albertine Sisters. He was her spiritual guide, and his letters to her document the strong bond between them. Suffused with curious sentimentality, his language there is full of diminutives, and he often refers to himself as her “daddy.” The contents of the letters suggest that he indeed adopted a fatherly attitude toward Sister Bernardyna, counseling her, consoling, and supporting, admonishing and praising, reminding her to take care of her health when needed, and constantly telling her to abandon her doubts and worries and surrender to God’s will. Reading these letters one is struck by the depth of his feelings for her and his overwhelming concern for her spiritual development. His advice is always practical and no-nonsense, and permeated by faith in God’s love.

His few notebooks show a slightly different aspect of his growing personality. They are the voice of his conscience and record his continuing inner struggles with sin, work at self-perfection and longing for God. His motto at this period of his life was: “If I learn that something is more perfect, I’ll do it.” His struggles focus on battling sins of laziness, gluttony, and procrastination. He chastises himself for wasting time on such activities as reading newspapers, smoking, talking about inconsequential matters; not concentrating hard enough on prayers and his search for God, not persevering in his program of self-perfection. This program of spiritual development was based on imitation of Christ’s love:

“The habitual desire to imitate Jesus – to meditate on his life so that in every situation I can behave as he would.

If something pleasurable to the senses appears, but it does not directly lead to glory and love of God, one should abandon it for the love of Jesus. (…) A radical medicine, and the source of virtues and good deeds is mortification and pacification of four natural desires:

Joy, hope, fear and pain; from their harmonization and pacification there arises all good. That’s why one should strive to deprive senses of all satisfaction, leave them as if in the vacuum and darkness, then one will see progress in virtue. Examples – that’s where the soul should be directed:

Not to what is tasteful, but to what’s distasteful.

Not to what one likes, but to what one dislikes.

Not to what brings one consolation, but to what brings despair.

Not to rest, but to work.

Not to demand more, but demand less.

Not what’s more refined and expensive, but what’s lower and more despised.

Not to wanting something, but to not wanting anything.

Not to look for the better in each thing, but to demand what’s worse for the love of Jesus, a complete nakedness, perfect spiritual poverty and absolute renouncing of all that’s of this world. Through wise and careful efforts one will find in this unspeakable joys and great sweetness. This is enough to enter the night of the senses.” (Kaczmarzyk, 1990, p. 157)

As we see in the above, Brother Albert’s attempts at self-perfection were aimed at cleansing the senses and achieving inner emptiness – a state of purification deepened by humility — which would be filled by God’s will and love. This was the soul’s path from the natural to supernatural, a path guided by grace, and devoted to serving others.

“Virtue is a practical knowledge of God and oneself. (…) One should ask for permission to completely surrender to spiritual pursuits because of oneself and one’s brothers and temptations, to strive for perfection and nothing else. Read, pray, learn. Love of oneself and one’s will are obstacles to perfection. One should perform one’s spiritual duties constantly, devotedly, completely.”(ibid., p. 159)

“One should act energetically generously and high-mindedly, constantly.” (ibid., p.158)

“Great efforts, attempts to complete ordinary tasks. Conditions: pure intent, devotion, time. Methods: depending on the author. Daily order, examination after each task. To undertake each task as if it were the last one in life.” (ibid., p.159)

Not incidentally, many of his notebook entries focus on his inner fight with effects of his sensual and psychomotor OE – his tendencies to dissipation, procrastination and wasting time; a lack of concentration; indulging in little sensual pleasures such as admiring some image of beauty not associated with God, or idle conversations. “Lack of concentration. Without concentration no one can achieve perfection. God’s presence – methods: if possible, to remain immobile, observe silence, avoid activities, which bring dissipation, frequently perform acts of love and faith.” (ibid., p.159) Judging by the contents of his diaries, his inner work and self-examination at that time took on somewhat obsessive character, guided by his acutely sensitive conscience.

Can we say that Brother Albert achieved the level of personality? His development, although radically advanced, was obviously not completed – if such a completion can ever take place — at the time of his death in December 1916. His notebooks from the last period of his life present a picture of inner struggles focused increasingly on realizing his plan of spiritual development and achieving perfection — not for the sake of perfection itself, but for the chance of achieving unity with God. It appears that he came as close to this goal as it is humanly possible.

Dabrowski describes the borderline of levels 4 and 5 as free of inner conflict, full of harmony, governed by the dynamisms of responsibility, authentism, autonomy, empathy, self-perfection and personality ideal. Although little is known about what one’s everyday life looks like on level 5, we can only speculate that, human mind being prone to dissipation, the efforts at self-perfection do not and cannot stop and must continue. But their developmental context changes, most notably in that it is free of inner conflict characteristic of earlier levels of development. Dabrowski says, “Secondary integration – this is where the greatest harmony appears on the way to personality and its ideal – and then perhaps new disruptions and perhaps new sensitivity, but not anymore to voices and whispers of transcendence but to its distinct reality.” (Dabrowski, 1972, p.27)

Brother Albert’s last years of life provide evidence that indeed he achieved the highest level of development. Quite clearly, his life embodies Dabrowski’s ideals of the highest level of sainthood, described in “Fragments from the Diary of a Madman:”

“There is a third holiness – according to me the highest one – which consists of involving oneself in the lives of people and their struggles; it is a serious and relentless plan for the improvement of people’s lives, and it is without prize, reward or compensation. It is a tragic road of heroism and an uncompromising attitude. This road does not look for support in quietist and detached experiences. The way is through atrophy of egoism. It is an enthusiastic though painful ascent to bring as much goodness and love as is possible to those who are suffering, hurt and humiliated.” (Dabrowski, p.49)

References:

Dabrowski, K., Kawczak, A., Sochanska, J. (1973). The Dynamics of Concepts. Gryf Publications, London.

Dabrowski, K. (under pseud. Paul Cienin), (1972). Existential Thoughts and Aphorisms. Gryf Publications. London.

Dabrowski, K. (under pseud. Paul Cienin), (1972). Fragments From the Diary of a Madman. Gryf Publications, Ltd. London.

Dabrowski, K. (1996). Multilevelness of Emotional and Instinctive Functions. KUL, Lublin.

Kaczmarzyk, M. (1990). Trudna Milosc. Swiety Brat Albert. SS. Albertynki, Krakow.

Kluz, W. (1981). Adam Chmielowski, Brat Albert. Wydawnictwo Apostolstwa Modlitwy, Krakow.

Ryn, Z. (1987). Brat Albert Chmielowski. Refleksje Psychiatryczne. In: Archiwum Historii i Filozofii Medycyny, 50, 4. Krakow.

All translations from the Polish by E. Mika.

____________________

Powyższe opracowanie zostało zaprezentowane podczas VI Międzynarodowego Kongresu Teorii Dezintegracji Pozytywnej Dąbrowskiego w Czerwcu 2004, w Calgary (Kanada)

Publikacja na stronach dezintegracja.pl za zgodą autorki.

![O kryzysie globalnym w świetle teorii dezintegracji pozytywnej Kazimierza Dąbrowskiego i teorii uczuć Daniela Golemana [PL]](https://dezintegracja.pl/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/3912002375_9c559d0ccb_z.jpg)

![CREATIVITY AND MENTAL HEALTH IN THE PROCESS OF POSITIVE DISINTEGRATION (paper for the 5th International Conference on The Theory of Positive Disintegration, USA, Florida, August 2002) [EN]](https://dezintegracja.pl/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/2849400717_a4008b5d59_z.jpg)

![Theory of Positive Disintegration as a Model of Personality Development For Exceptional Individuals [EN]](https://dezintegracja.pl/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/5509884998_e02f8c1abd_b.jpg)